The Maya, Aztec and Inca civilizations occupied relatively small areas and, compared to other Empires, had little affect over small numbers of people. However singly and combined, they developed extraordinary cultures with the only known fully developed writing system of the time, as well as for art, architecture, mathematical, agricultural [corn, peppers, potatoes, chocolate, tobacco and tomatoes] and astronomical systems. God knows what Europeans ate before the New World was discovered.

Initially established about 2000 BC many Maya cities reached their highest state of development from 250 to 900, and continued until the arrival of the Spanish. The Maya civilization shares many features with other Mesoamerican civilizations due to the high degree of interaction and cultural diffusion that characterized the region. Advances such as writing, epigraphy, and the calendar did not originate with the Maya; however, their civilization fully developed them.

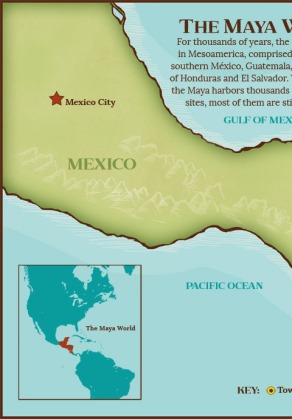

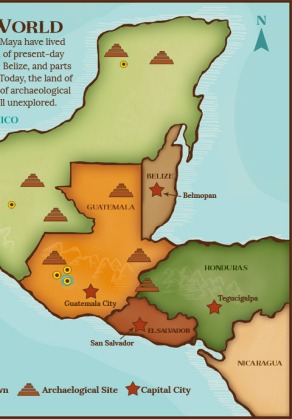

The Maya civilization extended throughout the present-day southern Mexican states and extended throughout the present day nations of Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. The people developed an agriculturally intensive, city centred civilization consisting of numerous independent states. This includes Caracol, Tikal, Palenque, Copán, Xunantunich and Calakmul, among others. During this period the Maya population numbered in the millions.

They created a multitude of kingdoms and small empires, built monumental palaces and temples, engaged in highly developed ceremonies, and developed an elaborate hieroglyphic writing system. The Maya civilization participated in long distance trade with many of the other Mesoamerican cultures and other groups in central and gulf coast Mexico. In addition, they had trade and exchanges with more distant, non-Mesoamerican groups, for example the Caribbean islands. Archaeologists have found gold from Panama in the Cenote of Chichen Itza[1]. Important trade goods included cacao, salt, seashells, jade, and obsidian.

Shortly after their first expeditions to the region, the Spanish initiated a number of attempts to subjugate the Maya who were hostile towards the Spanish crown. This campaign, sometimes termed “The Spanish Conquest of Yucatán”, would prove to be a lengthy and dangerous exercise for the conquistadores from the outset, and it would take some 170 years and tens of thousands of Indian auxiliaries before the Spanish established substantive control.

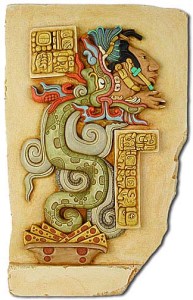

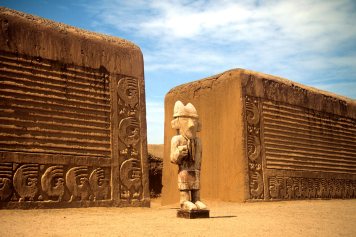

Maya art of the Classic era [c. 250 to 900 AD] is of a high level of aesthetic and artisanal sophistication, from the lay-out and architecture of court towns down to the decorative arts. The stucco and stone reliefs of Palenque and the statuary of Copán, particularly its impressive stelas, show a grace and accurate observation of the human form that reminded early archaeologists of Classical civilizations of the Old World. There are a number of examples of the advanced mural painting of the Classic Maya, most completely preserved in a building at Bonampak[2]. A rich blue colour (‘Maya Blue’) survived through the centuries due to its unique chemical characteristics.

Of the many folding books, only three survive, of which the Dresden Codex[3] is artistically superior. With the progressive decipherment of the Maya script, it was also discovered that the Maya were one of the few civilizations where artists attached their name to their work. Depending on the location of natural resources such as fresh-water wells, or cenotes, the city grew by using sacbeob [limed causeways] to connect great plazas with the platforms that created the sub-structure for nearly all Maya buildings. At the heart of the Maya city were large plazas surrounded by the most important buildings, such as the royal acropolis, great pyramid temples and occasionally ball-courts.

An integral aspect of the Mesoamerican lifestyle, the courts for their ritual ball-game were constructed throughout the Maya realm. Enclosed on two sides by stepped ramps that led to ceremonial platforms or small temples, the ballcourt itself was of a capital “I” shape and could be found in all but the smallest of Maya cities.

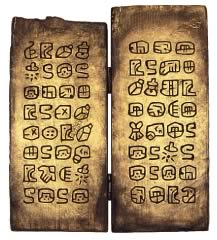

The Maya writing system [often called hieroglyphs from a superficial resemblance to the Ancient Egyptian writing] was a combination of phonetic symbols and logograms. It is the only writing system of the Pre-Columbian New World which is known to represent the spoken language of its community. In total, the script has more than a thousand different glyphs. National Geographic published the findings of Maya writings that could be as old as 400 BC. In the succeeding centuries the Maya developed their script into a form which was far more complete and complex than any other that has yet been found in the Americas.

Although many Maya centres went into decline or were completely abandoned during or after this period, the skill and knowledge of Maya writing persisted among segments of the population, and the early Spanish conquistadors knew of individuals who could still read and write the script. Unfortunately, the Spanish displayed little interest in it, and as a result of the dire impacts the conquest had on Maya societies, the knowledge was subsequently lost, probably within only a few generations.

The Maya produced accurate astronomical observations; their charts of the movements of the moon and planets were used to predict eclipses and other celestial events such the heliacal and cosmic risings and settings of Venus. The accuracy of their astronomy and the “theoretical” calendar derived from it was superior to any other known seventeen hundred years ago. The Dresden Codex contains the highest concentration of astronomical phenomena observations and calculations of any of the surviving texts. Examination and analysis of this codex reveals that Venus was the most important astronomical object to the Maya, even more important to them than the sun.

In common with the other Mesoamerican civilizations, the Maya had measured the length of the solar year to a high degree of accuracy, far more accurately than that used in Europe as the basis of the Gregorian calendar. They did not use this figure for the length of year in their calendars, however; the calendars they used were crude, being based on a year length of exactly 365 days, which means that the calendar falls out of step with the seasons by one day every four years.

Observatories. The Maya were keen astronomers and had mapped out the phases of celestial objects, especially the Moon and Venus. Round temples, often dedicated to Kukulcan[4], are perhaps those most often described as “observatories” by ruin tour guides, but pyramids of other shapes may well have been used for observation as well. The night sky was considered a window showing all supernatural doings. The Maya configured constellations of gods and places, saw the unfolding of narratives in their seasonal movements, and believed that the intersection of all possible worlds was in the night sky.

There is a massive array of supernatural characters in the Maya religious tradition, only some of which recur with regularity. The life-cycle of maize lies at the heart of Maya belief. This philosophy is demonstrated on the belief in the Maya maize god as a central religious figure. The Maya bodily ideal is also based on the form of this young deity, which is demonstrated in their artwork. Although it was not quite as prominent in Mayan culture as the Aztecs, the Maya practiced human sacrifice to an extent. In some Maya rituals people were killed by having their arms and legs held while a priest cut the person’s chest open and tore out his heart as an offering. This is depicted on ancient objects such as pictorial texts, known as codices.

Within a century or so the flourishing Classic Maya civilization fell into a permanent decline, so that once great cities were abandoned and so disappear from human memory for centuries.

‘This was surely one of the most profound social and demographic catastrophes of all human history’.

The question, then, which has preoccupied scholars ever since the re-discovery in the 19th century CE of mysterious ruins built by, at the time, an equally mysterious civilization, is why did this happen? Disease, a social revolution, drought, famine, foreign invasion, over-population, disruption in trade routes, earthquakes, and even hurricanes were held responsible. From the mid to late 8th century CE relations between city-states deteriorated. There was a decline in trade and an increase in armed conflicts. We know that the death rate increased and from 830 CE no new buildings were constructed. As the Maya were fond of writing dates on their monuments and stelae, it is interesting to note that no dates after c. 910 CE are seen in the lowlands sites.

There is also evidence of large areas becoming completely depopulated and royal dynasties and elites disappearing without trace. The collapse was neither unique – smaller scale abandonment of Maya cities had occurred several times before over the centuries – nor was it sudden but rather a process of decline which occurred over a period of 150 years. An ever increasing population may well have driven the Maya to deforest areas which were subsequently eroded. Sapodilla was the architect’s choice for such details as lintels but was then replaced by the inferior wood. Had the Maya exhausted their supply of Sapodilla?

Maya historians have generally settled on a combination of three main factors which could have caused the Maya collapse: warfare between city-states, overpopulation, and drought. Warfare had been a part of Maya culture for centuries, but its intensification and scale increased prior to the collapse so that cities began to build fortifications. Previously, warfare had often been token, in that defeat might result in only a small number of important figures being taken as captives. The conquest of territory and the capture of sacrificial victims now became a priority – the former perhaps to increase agricultural production and acquire resources and the latter to appease the gods and return to the more stable times of earlier centuries.

Over-population may well have put an unbearable strain on the agricultural production; the Maya lowlands suffered a sustained series of droughts between 800 and 1050 CE. For those regions which did suffer a water shortage, the lack of rain and repeated crop failures make it entirely conceivable that either the lower levels of society – 90% of the population were farmers – rebelled against the ruling class. With the consequent collapse of the social structure and city infrastructure, those who could may well have migrated however there is no archaeological record of a large population movement, only that after the collapse, the 60,000 square miles of the Maya lowlands was deserted.

From the 13th century, the Valley of Mexico was the heart of Aztec civilization: here the capital of the Aztec Triple Alliance, the city of Tenochtitlan, was built upon raised islets in Lake Texcoco. The Triple Alliance formed a tributary empire expanding its political hegemony far beyond the Valley of Mexico, conquering other city states throughout Mesoamerica. At its pinnacle, Aztec culture had rich and complex mythological and religious traditions, as well as reaching remarkable architectural and artistic accomplishments.

It was never a true territorial empire with military garrisons in conquered provinces, but rather controlled its client states by installing friendly rulers in conquered cities, and by constructing marriage alliances between the ruling dynasties. Client states paid tribute to the Aztec emperor in an economic strategy making them depend on the imperial centre for the acquisition of luxury goods. The political clout of the empire reached far south into Mesoamerica conquering cities as far south as Guatemala and spanning from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans. The empire reached its maximal extent in 1519 just prior to the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors.

Two of the primary architects of the Aztec empire were the half-brothers Tlacaelel and Montezuma I. Tlacaelel reformed the Aztec state and religion. He rewrote the history of the Aztec people which led directly to the curriculum taught to scholars and promoted the belief that the Aztecs were always a powerful and mythic nation. One component of this reform was the institution of ritual war (the flower wars) as a way to have trained warriors, and created the necessity of constant sacrifices to keep the Sun moving.

Despite the decline of the Aztec empire, most of the Mesoamerican cultures were intact after the fall of Tenochtitlan. Indeed, the freedom from Aztec domination may have been considered a positive development by most of the other cultures. The upper classes of the Aztec empire were considered noblemen by the Spaniards and generally treated as such initially. All this changed rapidly and the native population were soon forbidden to study by law, and had the status of minors.

The conquistadors were professional warriors, using European tactics, firearms, and cavalry. Their units specialized in forms of combat that required long periods of training that were too costly for informal groups. Their armies were mostly composed of Iberian and other European soldiers. The two most famous conquistadors were Hernán Cortés who conquered the Aztec Empire and Francisco Pizarro who led the conquest of the Incan Empire. They were second cousins born in Extremadura, as were many of the Spanish conquerors.

In 1504, Cortés left Spain to seek his fortune in New World. He travelled to Hispaniola. Settling in the new town of Azúa, Cortés served as a notary for several years and joined an expedition of Cuba led by Diego Velázquez. In 1518, Cortés was to command his own expedition to Mexico, but Velázquez cancelled it. Cortés ignored the order and set sail for Mexico with more than 500 men and 11 ships, reach the Mexican coast in 1519. There, he encountered Geronimo de Aguilar, a Spanish Franciscan priest who had survived a shipwreck, and a period in captivity with the Maya, before escaping. Aguilar had learned the local language and was able to translate for Cortés.

In March 1519, Cortés formally claimed the land for the Spanish crown. Then he proceeded to Tabasco, where he met with resistance and won a battle against the natives. He received twenty young indigenous women from the vanquished natives and he converted them all to Christianity. Among these women was La Malinche, his future mistress and mother of his son Martín. Malinche knew both the Nahuatl language and the Chontal Maya, thus enabling Cortés to communicate with the Aztecs through Aguilar. At San Juan de Ulúa on Easter Sunday 1519, Cortés met with the Aztec Empire[5] governor’s. In July his men took over Veracruz. By this act, Cortés dismissed the authority of the Governor of Cuba to place himself directly under the orders of King Charles. In order to eliminate any ideas of retreat, Cortés scuttled his ships.

Cortés and his men, accompanied by about 1,000 Tlaxcalteca, marched to Cholula, where, either in a pre-meditated effort to instil fear upon the Aztecs waiting for him at Tenochtitlan or, wishing to make an example, massacred thousands of unarmed members of the nobility gathered at the central plaza, then partially burned the city.

On November 8 1519, they were peacefully received by Montezuma II[6] who deliberately let Cortés enter the Aztec capital, hoping to get to know their weaknesses and crush them later. Montezuma gave lavish gifts of gold to the Spaniards which, rather than placating them, excited their ambitions for plunder. In his letters to King Charles, Cortés claimed to have learned that he was considered by the Aztecs to be either an emissary of the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl or the god himself. Meanwhile, Velázquez sent another expedition, to oppose Cortés, arriving in Mexico with 1,100 men. Cortés overcame Narváez, despite his numerical inferiority, and convinced the rest of Narváez’s men to join him. In Mexico, one of Cortés’s lieutenants Pedro de Alvarado, committed The massacre in the Main Temple, triggering a local rebellion.

Montezuma was killed; the Spaniards claimed he was stoned to death by his own people. Faced with a hostile population, Cortés fled for Tlaxcala managing a narrow escape across the Tlacopan causeway, while their rear guard was being massacred. Much of the treasure looted by Cortés as well as his artillery was lost. With the assistance of his allies, Cortés finally prevailed with reinforcements arriving from Cuba. Cortés began a policy of attrition, cutting off supplies and subduing the Aztecs’ allied cities. The siege of Tenochtitlan ended with Spanish victory and the destruction of the city. Finally, with the capture of Cuauhtémoc,[7] the Aztec Empire disappeared, and Cortés claimed it for Spain, renaming it Mexico City.

King Charles appointed Cortés as governor, captain general and chief justice of “New Spain”. But also, much to the dismay of Cortés, four royal officials were appointed at the same time to assist him in his governing. Cortés initiated the construction of Mexico City, destroying Aztec temples and buildings and then rebuilding on the Aztec ruins what soon became the most important European city in the Americas. Cortés managed the founding of new cities and extended Spanish rule to all of New Spain, imposing the encomienda system in 1524. He reserved many encomienda for himself and for his retinue. Although Cortés had flouted the authority of Diego Velázquez in sailing to the mainland and then leading an expedition of conquest, his spectacular success was rewarded by the crown with a coat of arms.

In 1528, Cortés presented himself with great splendour before Charles V’s court. Denying he had held back on gold due the crown, he showed that he had contributed more than the quinto. He was decorated with the order of Santiago and was rewarded in 1529 by being named the “Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca”, one of the wealthiest region of New Spain, and Cortés had 23,000 vassals in 23 named encomienda in perpetuity. In 1536 Cortés explored the north-western part of Mexico and discovered the Baja California peninsula. Cortés also spent time exploring the Pacific coast of Mexico. The Gulf of California was originally named the Sea of Cortes by its discoverer Francisco de Ulloa in 1539. This was the last major expedition by Cortés. On December 4, 1547 he was buried in the mausoleum of the Duke of Medina in Seville. Three years later his body was moved and in 1566 sent to New Spain and buried in the church of “San Francisco de Texcoco”, where his mother and one of his sisters were buried.

The viceroy moved the bones of Cortés along with those of his descendants to the Franciscan church in México where they stayed for 87 years. In 1794, his bones were again moved to the “Hospital de Jesus” [founded by Cortés], where a statue by Tolsa and a mausoleum were made. In 1823, after the independence of México, it seemed that his body would be desecrated, so the mausoleum was removed, the statue and the coat of arms were sent to Palermo. It was not until 1946 that they were rediscovered and authenticated by INAH. When the bones were first rediscovered one supporter of an indigenous vision of Mexico “proposed that the remains be publicly burned in front of the statue of Cuauhtemoc, and the ashes flung into the air.”

Cortés and the “Spiritual Conquest” of Mexico.

During the Age of Discovery, the Catholic Church had seen early attempts at conversion in the Caribbean islands by Spanish friars, particularly mendicant orders. Cortés made a request to the Spanish monarch to send Franciscan and Dominican friars to Mexico to begin the work of converting vast populations indigenous to Christianity. In his fourth letter to the king, Cortés pleaded for friars rather than diocesan or secular priests because those clerics were in his view a serious danger to the Indians’ conversion.

Francisco Pizarro[8] was born, an illegitimate child, c 1476, in Trujillo, Spain, an area stricken by poverty. Pizarro grew up illiterate, and while herding his father’s pigs, heard tales of the New World and was seized by a lust for fortune and adventure. In 1510, he accompanied Spanish explorer Alonzo de Ojeda on a voyage to Colombia. He sailed to Cartagena and joined the fleet of Martín Fernández and, in 1513, accompanied Balboa to the Pacific. In 1514, he was rewarded for his role in the arrest of Balboa with the positions of mayor and magistrate in Panama City, serving from 1519 to 1523. Reports of Peru’s riches and Cortés’s success in Mexico tantalized Pizarro and he undertook two expeditions to conquer the Incan Empire in 1524 and in 1526. Both failed as a result of native hostilities, bad weather, and lack of provisions.

Pizzaro reached Seville in early summer of 1528. King Charles I, who was at Toledo, had an interview with Pizarro and heard of his expeditions in South America, a territory the conquistador described as very rich in gold and silver which he and his followers had bravely explored “to extend the empire of Castile.” The Kingwas impressed and promised to give his support for the conquest of Peru. It would be Queen Isabel, however, who, in the absence of the King, would sign the Capitulación de Toledo a license which authorized Francisco Pizarro to proceed with the conquest of Peru. Pizarro was officially named the Governor, Captain general, “Adelantado”, and Alguacil Mayor, of the New Castile for the distance of 200 leagues along the newly discovered coast, and invested with all the authority and prerogatives, his associates being left in wholly secondary. One of the conditions of the grant was that within six months Pizarro should raise a sufficiently equipped force of two hundred and fifty men, of whom one hundred might be drawn from the colonies.

Those who decided to stay with Pizarro and later became known as “The Famous Thirteen“ while the rest of the expedition left. When a Dominican friar explained the need to pay tribute to the Emperor, Atahualpa, replied “I will be no man’s tributary.” His complacency, because there were fewer than 200 Spanish as opposed to his 50,000 man army sealed his fate and that of the Incan empire. The Spanish entered Cuzco on 15 Nov. 1533. Pizarro founded the city of Lima in Peru’s central coast, an act he considered as one of the most important things he had created in life. Over time, tensions increasingly built up between the conquistadors who had originally conquered Peru and those who arrived later. As a result, conquistadors divided into two factions, one run by Pizarro, and the other Almagro. Hernando Pizarro captured and executed Almagro, three years later in Lima, members of the defeated party avenged Almagro’s death by assassinating Francisco Pizarro.

De Soto[9] sailed to the New World in 1520 and participated in Gaspar de Espinosa’s expedition to Veragua, and in the conquest of Nicaragua under Francisco Hernandez de Cordoba. There he acquired am encomienda and a public office in Nicaragua. Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and ruthless schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto’s hallmarks during the Conquest of Central America. He gained fame as an excellent horseman, fighter, and tactician, but was notorious for the brutal treatment of Native Americans.

The Inca Empire: Children of the Sun

When Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro landed in Peru in 1532, he found unimaginable riches. The Inca Empire was in full bloom. The streets may not have been paved with gold, but their temples were. The Coricancha, or Temple of Gold, boasted an ornamental garden where the clods of earth, maize plants complete with leaves and corn cobs, were fashioned from silver and gold. Nearby grazed a flock of 20 golden llamas and their lambs, watched over by solid gold shepherds. Inca nobles strolled around on sandals with silver soles protecting their feet from the hard streets of Cuzco.

The Inca called their empire Tahuantinsuyu[10], or Land of the Four Quarters. It stretched 2,500 miles from Quito, Ecuador, to beyond Santiago, Chile. Within its domain were rich coastal settlements, high mountain valleys, rain-drenched tropical forests and the driest of deserts. The Inca controlled perhaps 10 million people, speaking a hundred different tongues. It was the largest empire on earth at the time. The administrative, political, and military centre of the empire was located in Cusco. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century, and the last Inca stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572. Yet when Pizarro executed its last emperor, Atahualpa, the Inca Empire was only 50 years old. The Inca Empire was an amalgamation of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. The Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour.

The following quote reflects a method of taxation:

“For as is well known to all, not a single village of the highlands or the plains failed to pay the tribute levied on it by those who were in charge of these matters. There were even provinces where, when the natives alleged that they were unable to pay their tribute, the Inca ordered that each inhabitant should be obliged to turn in every four months a large quill full of live lice, which was the Inca’s way of teaching and accustoming them to pay tribute”.

Estimates of the number of people inhabiting Tawantinsuyu at its peak range from as few as 4 million people, to more than 37 million. The reason for these various estimates is that in spite of the fact that the Inca kept excellent census records using their quipu, knowledge of how to read them has been lost, and almost all of them had been destroyed by the Spaniards in the course of their conquest.

Andean civilization probably began about 7600 BCE. Based in the highlands of Peru, an area now referred to as the punas, the ancestors of the Incas began as a nomadic herding people. Geographical conditions resulted in a distinctive physical development characterized by a small stature and stocky build. Men averaged 1.57 m and women averaged 1.45 m. Because of the high altitudes, they had unique lung developments with almost one third greater capacity than other humans. The Incas had slower heart rates, blood volume of about 2 litres more than other humans, and double the amount of haemoglobin which transfers oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

Archaeologists have found traces of permanent habitation as high as 5,300 m above sea level in the temperate zone of the high altiplano. While the Conquistadors may have been a little taller, the Inca surely had the advantage of coping with the extraordinary altitude. It seems that civilizations in this area before the Inca have left no written record, and therefore the Inca seem to appear from nowhere, but the Inca were a product of the past. They borrowed architecture, ceramics, and their empire-state government from previous cultures.

When Pizarro returned to Peru in 1532, a war of the two brothers between Huayna Capac’s sons and unrest among newly conquered territories, and perhaps more importantly, smallpox, which had spread from Central America, had considerably weakened the empire. The Spanish horsemen, fully armoured, had great technological superiority over the Inca forces. The traditional mode of battle in the Andes was a kind of siege warfare where large numbers of draftees were sent to overwhelm opponents.

Architecture was by far the most important of the Inca arts, with textiles reflecting motifs that were at their height in architecture. The main example is the capital city of Cusco. The site of Machu Picchu was constructed by Inca engineers. The stone temples constructed by the Inca used a mortar-less construction that fit together so well that a knife could not be fitted through the stonework. After the fall of the Inca Empire many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed, including their sophisticated farming system, known as the ‘vertical archipelago’ model of agriculture. Spanish colonial officials used the Inca labour system for colonial aims, sometimes brutally. One member of each family was forced to work in the gold and silver mines, the foremost of which was the titanic silver mine at Potosí. When a family member died, which would usually happen within a year or two, the family would be required to send a replacement.

The effects of smallpox on the Inca empire were even more devastating. Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Within a few years smallpox claimed between 60% and 90% of the Inca population, with other waves of European disease weakening them further. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, measles in 1618 – all ravaged the remains of Inca culture.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_Cenote

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonampak

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dresden_Codex

[4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kukulkan

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aztec_Empire

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moctezuma_II

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuauhtémoc

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Pizarro